Remembering the Not-So-Forgotten War: Korean War Stories of Service in the Navy Log

The Navy Log features Stories of Service that span the history of the nation’s Sea Services. Tales of war and of peace are remembered alongside one another in the Navy Log, and each service member’s service has their own unique tales to tell within this rich history. Throughout the year, anniversaries of battles, events, and achievements offer special opportunities to showcase some of these tales in context. Tales from the Navy Log will take some time on some of these dates to do just that.

The Korean War is permanently memorialized on the National Mall in the center of our nation’s capital in a memorial that was dedicated in 1995. In this memorial, located just across the Reflecting Pool from the Vietnam War Memorial, 19 statues of Korean War troops make their way towards the American flag. The memorial’s ambiance is particularly somber at night.

On July 27, following annual executive proclamation, the United States observes National Korean War Veterans Armistice Day. Today this national day of observance, which takes place on the anniversary of the armistice signed between the conflict’s warring nations, is meant to remember those service members who gave their lives in the Korean War. In America’s public memory, the Korean War is too frequently the conflict of the twentieth century that receives the least attention. As the nation has marked the 100th anniversary of World War I and the 75th anniversary of World War II over the last several years, this inconsistency has become more apparent. In fact, the Korean War is frequently referred to as the “Forgotten War,” which is a particular tragedy for the more than 36,000 Americans who gave their lives during the conflict. For this reason, concerted efforts to commemorate the service of Korean War veterans is crucial, and events like this day are important steps to take to break down this discrepancy.

To mark National Korean War Veterans Armistice Day, Tales from the Navy Log will highlight some Stories of Service from a few Korean War veterans within our records that we recently came across. It also encourages its readers to search through the Navy Log for themselves and find some more of the thousands of Stories that our Korean War veterans have to tell.

Before the start of the conflict, the 38th Parallel was a much softer border that separated two nations under different international influences. By 1950, the border was at the center of a conflict that brought international intervention.

Before bringing attention to several Stories of Service from the Korean War from the Navy Log, some brief context is needed about the conflict itself. Following World War II, the Korean Peninsula was divided in a northern and southern half along the 38th Parallel, with the two halves reorganized into different circles of influence. In June 25, 1950, forces from North Korea, whose government was under communist influence, attacked the democratic South Korea, sparking the first crisis for the newly formed United Nations. Two days later, the United States urged the UN to intervene, and those nations in attendance agreed. Before reinforcements could arrive, on June 28, the South Korean capital of Seoul had fallen into the hands of the rapidly advancing Communist forces from the North. If the United States could not rescue South Korea from this assault, America’s allies could lose confidence in the nation’s capability to offer the protection it promised to provide. American leaders also feared that this act of communist aggression, if left unchecked, would enable additional acts of communist aggression elsewhere across the globe, each of which could similarly threaten American global influence. After losing over 400,000 service members in World War II just five years earlier and demobilizing wartime production to return to a peacetime economy, American military strength and readiness were not prepared to resist this assault alone. Fortunately, seventeen UN member nations, including the US and South Korea, sent military forces to Korea to stop this Communist invasion.

These troops dig into a defensive outpost to secure a perimeter around the UN landing site near Pusan.

Following the armistice, the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea has remained a volatile site. The checkpoints are always monitored, and the tension at them has not fully subsided.

In early July, the first American and UN troops arrived on the Korean Peninsula. Establishing an initial foothold was a long and bloody process, but eventually a perimeter was established around the southern port of Pusan. By the end of August, reinforcements arrived, and General Douglas MacArthur took command of the force. Through the fall, MacArthur orchestrated an amphibious assault on Inch’on, a port located behind North Korean lines, to break Communist positions with an unexpected attack. His plan was risky, but it payed off, capturing the landing zone and then moving south towards Seoul. Meanwhile, other forces pushed northward from their perimeter onto the capital as well, which was taken back by both forces by September 27. With this victory, North Korean forces were no longer organized in the south, and the South Korean government and border were restored by the end of the month. From there, MacArthur’s forces kept the offensive and pushed northward in October to capture the North Korean capital of Pyongyang. However, this action drew a response from Communist Chinese Forces (CCF) to the peninsula’s north. By November, UN forces pushing northward began encountering Chinese divisions offering fierce opposition and attempting to surround them, forcing the UN troops to retreat to Seoul. In early 1951, reorganized UN forces launched a successful counteroffensive to gain lost ground back just beyond the 38th Parallel and established a defensive line there. In late spring, Chinese forces attempted to push through these lines, but were unsuccessful. On July 10 of that year, the first rounds of armistice talks began, but the Communists broke off negotiations in August over disputes about the current border between North and South. Shortly thereafter, Communist forces resumed their offensive and pushed back UN forces slightly. This pattern of attempts at peace talks stagnating and giving way to resumed hostilities continued through 1952 and into 1953. Finally, the negotiations through July succeeded, and an armistice was signed on July 27, 1953. The ceasefire demarcation line reflected the territory controlled by each side at the end of fighting and was close to the 38th Parallel, although North Korea had lost 1,500 square miles of territory. The agreement specified that both sides had to withdraw two kilometers away from the ceasefire line to deter further skirmishes, establishing a demilitarized zone between the two nations that still exists to this day.

After three years of fighting, the Korean War had reached an uneasy conclusion with an armistice that roughly reestablished the prewar boundary between North and South Korea. Technically, the conflict never officially came to an end, as the stalemate did not result in any formal peace settlement after the fact. For this reason, some saw the Korean War as a stalemate at best, if not a defeat by some detractors. However, today historians agree that our troops did succeed in their primary objective: South Korea remained free from Communist rule.

While some African Americans had seen combat in World War II, they did so in segregated units. By the Korean War, the military had made huge strides to desegregate its units in response to an Executive Order from President Harry Truman, allowing for African Americans to serve alongside white service members. Although many still experienced racism through other institutionalized and personal acts of discrimination, this act was a huge step in civil rights and a significant positive for military readiness.

Through the war’s duration, over one and a half million American service members took part in the fight in a diverse portfolio of roles. This was also the first war that America fought after the military’s racial desegregation in 1948, meaning that the Korean War was the first conflict where Americans served truly alongside one another regardless of race. Sea Service personnel participated in a wide variety of roles throughout the campaign. Navy ships successfully blockaded the North Korean port of Wonsan throughout the war, fought several skirmishes at sea with Communist naval forces, and supported amphibious assaults and other land actions on the mainland. Marines spearheaded amphibious actions at Inchon and fought throughout the duration of the war across the peninsula, including the hard-fought battle of the Chosin Reservoir now immortalized in Marine Corps lore. Navy Seabees were tasked with supporting amphibious landings and constructing usable airfields for close air support missions and medical evacuations. Navy and Marine pilots flew more close air support missions for ground forces than ever before, with great success. Coast Guard ocean stations and Long-Range Aids to Navigation (LORAN) stations in Pusan and across the region provided essential and unprecedented levels of support for UN naval and air vessels planning and navigating actions nearby. Today, Tales from the Navy Log will commemorate the service of all Korean War veterans of the Sea Service by sharing the story of just a few of the Korean War veterans.

Of course, the “Navy” Log features its fair share of Navy veterans, a large number of which saw service in the Korean War. Throughout the war, the Navy had a wide variety of essential roles to play in the conflict, and each sailor’s duty was vital for mission success. One of these sailors was CAPT Richard Lynn Teaford. As a Midshipman, Teaford was assigned as a Line Officer to the USS Los Angeles CA-135, which was assigned to the Seventh Fleet during the war. By the end of the conflict, the ship had earned five battle stars. On April 1, 1953, the cruiser competed a 31 consecutive day siege on the port of Wonson, firing a total of 17,000 rounds on the harbor’s positions. The day after, an enemy shell from a shore battery in Wonson Harbor hit the ship’s mainmast, wounding twelve and forcing the ship to repair. Before the end of the war, Teaford also recalled being able to visit his brother, Supply Officer LTJG Sidney Teaford, at-sea aboard the carrier USS Oriskany CVA-34. To learn more about CAPT Teaford’s Sea Service, visit his Navy Log.

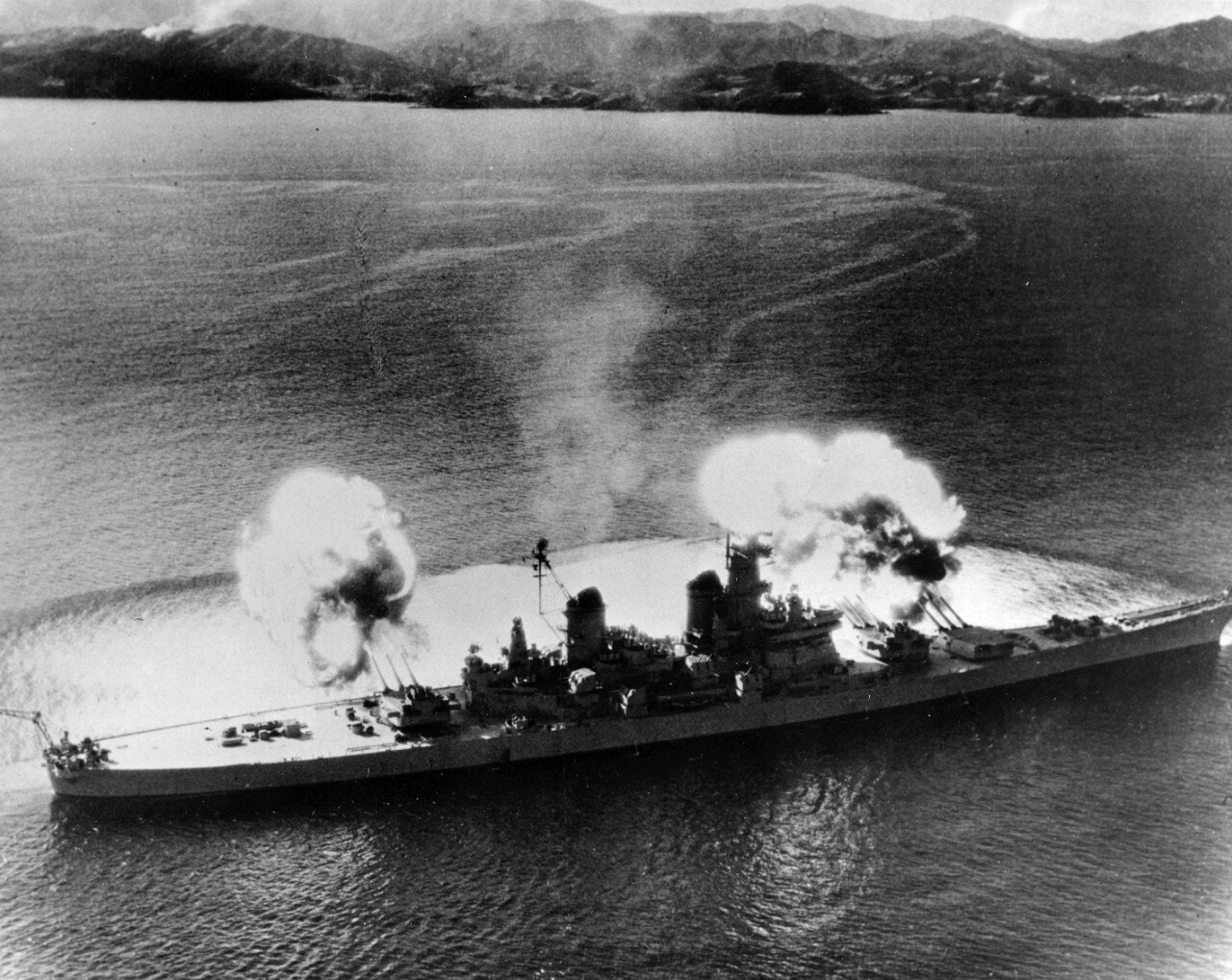

The nine 16-inch guns onboard the USS New Jersey carry out bombardment operations against enemy targets near the 38th Parallel in November 1951. Smoke emanating from the ship’s target can be seen in the image’s upper left.

The Navy Memorial Interview Archive also contains recorded conversations with many Navy veterans of the Korean War within its database. One of these many interviews is that of John Bibeault, who served aboard the USS Missouri during the war as an electrician’s mate. His five-part interview archive is preserved within the Navy Memorial Interview Archive and offers a fascinating perspective of the Korean War from the sea.

Part One Summary of Service

Part Three The USS Missouri and the Korean War

Part Five Des Moines and Operation Mariner

Part Two Joining the Navy and service on the USS Missouri during the Korean War

Part Four Service on the USS Des Moines

These Corsair fighters prepare for takeoff from the flight deck of the USS Philippine Sea, which was operating off the southwest coast of the Korean Peninsula.

The previous Tales from the Navy Log blog actually featured two Marine aviators who both flew combat missions in the Korean War: Jerry Coleman and Ted Williams. As aviators, these Marines flew close combat missions in support of UN troops on the ground, taking out enemy positions and strongholds that threatened friendly troops. These actions demanded extensive communication between air and ground forces to prevent accidental friendly casualties. Advances in radar, communications, aircraft, and tactics improved all improved American airpower, each of which improved the possibilities of close air support missions. To learn more about their roles in the war, make sure to check out our previous blog.

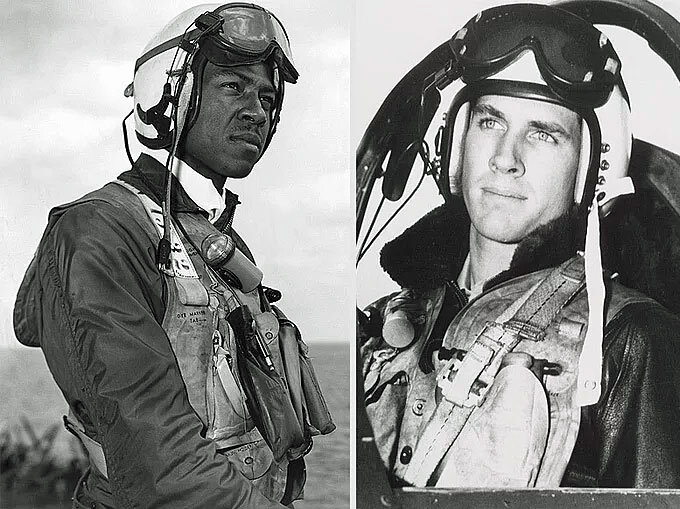

Thomas Hudner, on right, served in the same Fighter Squadron as Jesse Brown, on left. After the war, Hudner never gave up his search for his fallen comrade, whose remains were not recovered.

Tales from the Navy Log also wants to showcase two Naval aviators whose Korean War service is memorialized in the Navy Log: CAPT Thomas J Hudner Jr. and ENS Jesse L. Brown. After serving in World War II, Hudner attended the U.S. Naval Academy and graduated with the Class of 1947. That same year, Brown, who had joined the Naval Reserve to help pay for college, received orders to attend flight training; at 22, Brown was the first African American man to complete Navy Flight Training. During the Korean War, both men served as Corsair pilots assigned to the USS Leyte. On December 4, 1950, Hudner and Brown were flying a mission over the Chosin Reservoir when Brown was forced down behind enemy lines after being hit by antiaircraft fire. After circling his downed comrade with his plane to fight off incoming enemy troops, Hudner force landed his own plane on the rough and mountainous terrain. Once on the ground, Hudner packed Brown’s burning fuselage with snow to smother the flames and radioed other airborne planes for help. Tragically, Hudner was unable to free Brown from the mangled cockpit, and Brown died after telling Hudner to tell his wife he loved her. Brown was the first African American naval officer killed in the Korean War, and he posthumously received the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal, and the Purple Heart. Expecting a court martial for bringing down his plane under enemy fire, Hudner instead received the Medal of Honor for his conspicuous and selfless gallantry in the face of danger to attempt to save a comrade. Hudner and Brown are both honored within the Navy Log. The Navy Memorial’s Interview Archive also had the incredible honor to speak with CAPT Hudner before he passed away, and his five-part interview can be found below:

Part One Memories of World War Two and Attending the United States Naval Academy

Part Three Missions During the Korean War and Ensign Jesse Brown

Part Five Returning to the USS Leyte CV 32 and Memories of the Korean War

Part Two Joining Fighter Squadron 32 and Service on the USS Leyte CV 32

Part Four The Loss of Ensign Jesse Brown

These Marines disembark from their landing craft onto the shores near Inch’on. The Marine amphibious assault is also the action that was selected to be depicted on the Marine Corps’ bronze relief at the Navy Memorial.

From the initial amphibious invasions, through the back and forth offensives across the peninsula, to the stalemate and armistice at the 38th Parallel, the Marine Corps played a central role in the ground war of the Korean War. The first instance of the Marines’ involvement in the war was their role in the Inch’on invasion. On September 15, 1950, the Marines hit the three designated landing beaches to a surprised North Korean defense force. Despite the reefs and shoals that littered the seawall, the Marines experienced little geographical difficulties coming ashore, and the landings went off without a hitch. By the end of the first day, the city was almost entirely subdued. The city’s Kimpo Airfield became a battlefield by the next day, as more Marines and some Army troops reinforced the initial landing waves. From this landing, the American and UN forces, spearheaded by the Marines, succeeded in their ultimate objective: Seoul was reclaimed by the end of the month.

Of the many Marines that fought at Inch’on and are now honored in the Navy Log, Tales from the Navy Log hopes to highlight the service of LT Baldomero “Baldy” Lopez. After graduating from the Naval Academy in 1947, Lopez joined the Marine Corps. On the day of the invasion of Inchon, LT Lopez was serving as a rifle group commander in A Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines in the 1st Marine Division. His platoon was charged with reducing the enemy beach defenses during the assault. Lopez moved forward towards an enemy bunker whose fire was pinning down his section of the beach. As he wound back to throw a grenade, he was hit by enemy automatic weapon fire in his right shoulder and chest, which caused him to fall and drop the grenade. Lopez dragged himself towards the grenade to throw it away, but his blood loss hindered his ability to grasp the grenade firmly enough to throw it. In that moment, Lopez instead cradled the grenade with his right arm and under his body to absorb its full blast, choosing to sacrifice himself rather than endanger the lives of his fellow Marines. This exceptional act of gallantry and selflessness posthumously earned Lopez the Medal of Honor. Lopez’s Navy Log, which includes his Medal of honor citation, can be found here.

The Frozen Chosin did not earn their nickname easily. These Marines were very literally freezing in the brutal subzero temperatures of the mountainous terrain. Frostbite was effectively a more dangerous enemy than the enemy’s gunfire.

The Marines’ greatest battle during the Korean War took place as UN forces were withdrawing southward down the peninsula. Chinese Communist Forces pushed into North Korea in the winter of 1950 to fight back the unsuspecting UN forces. With this counteroffensive, the 1st Marine Division, who had been pushing hard in their drive north and had thousands of casualties to tend to, found themselves surrounded with some other Army units in a harsh and remote position near a large reservoir named Changjin in North Korea, some 70 miles away from the sea and far away from friendly lines. The Marines who fought near the reservoir ignored its Korean name in favor of its Japanese one: Chosin. Chinese forces were relentless in trying to break the Marine defenses and annihilate the remaining Marines. Despite this onslaught, the Marines, low on gear and vastly outnumbered, dug into the unsuitable terrain and prepared to fight to the last man. To make matters worse, the winter of 1950 was one of the coldest ever recorded in the area, so cold that the ground was too frigid for the Marines to dig proper foxholes. Given the terrible weather conditions they faced in this brutal struggle, the Marines adopted a nickname for themselves: the “Frozen Chosin” Marines. Feet froze in boots in the subzero weather, and even wounds froze closed, but the Frozen Chosin fought on. No Marines had ever fought under worse conditions of weather and terrain. After several days under siege, the Frozen Chosin began to fight for their lives towards the sea, with heavy support from the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. Their push succeeded thanks to incredible willpower, tactics, and valor, as the Marines held off the attacking Chinese forces, escaped to the coast for rescue, and brought out their dead and wounded. Today, the 17-day Battle of Chosin Reservoir is immortalized in Marine Corps lore as a testament to Marine fighting spirit and valor.

A large number of Frozen Chosin Marines are honored in the Navy Log today. Among these names is COL William Earl Barber. After seeing combat on the shores of Iwo Jima during World War II, Barber also served in the Korean War as a captain. When the Chinese Communist Forces encircled the 1st Marine Division, Barber was serving as the commanding officer of F Company in 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines. As the Marines desperately pushed towards the sea to escape, Barber led his company in a valiant five-day defense of a three-mile mountain pass that was vital to their supply line and withdrawal to the sea. While bitterly defending this pass against overwhelming enemy action, Barber was severely wounded in his leg on the morning of November 29th, yet he remained in control and continued to heroically command his Marines, often moving up and down his lines on a stretcher to direct defense and encourage and inspire his men. Against overwhelming odds, he and his unit held their positions until relieved, although only 82 of his original 220 men were able to walk away from their positions. Once evacuated, Barber at last received medical attention onboard a Navy hospital ship. His valorous leadership and his men’s supreme gallantry earned Barber the Medal of Honor. To learn more about Barber’s unbelievable Stories of Service, make sure to check out his Navy Log here.

Not every Marine who fought in the Battle of Chosin Reservoir was so lucky. Private First Class Richard Stanley Gzik, for example, was serving with the 11th Artillery Regiment’s M Company with the 1st Marine Division when his unit found itself surrounded near Chosin. On December 2, 1950, Gzik was killed in action. His body was at first unable to be recovered due to the unit’s withdrawal, so he was buried alongside the road. Gzik’s remains were among those exchanged with Communist forces in 1954, although his were at first unable to be identified and were interred at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii. In 2012, analysts were able to at last identify Gzik’s remains, allowing for him to return to his family for proper burial with full military honors. To learn more about PFC Gzik’s service, please visit his Navy Log.

The Marines were not the only service members to take place in the battle of Chosin Reservoir. Several smaller Army units and isolated soldiers that were separated from their units were also surrounded with the Marines and had to fight alongside them throughout the battle. When the Marines deploy, they do so with support staff and medical personnel from the Navy, since the Marines do not have their own medical corps. This meant that many Naval Corpsmen were also to endure the harsh winter and combat environment of the battle. Among these medical staff with the Marines was Dr. Stanley Wolf, who was a Lieutenant, junior grade assigned to support the 1st Marine Division during the war. Before the battle of Chosin Reservoir, Wolf earned the Bronze Star for tending to wounded Marines under fire near Inchon. In his six-part interview in the Navy Memorial Interview Archive, Wolf remembered his experience near the Chosin Reservoir. Wolf remembers how difficult it was treating the literally frozen casualties that came to his aid station for treatment and evacuation to rear aid stations in the rear under extreme cold temperatures and limited medical equipment. He was also wounded by mortar fire while tending to other wounded troops, but remained treating Marines and soldiers in the field and preparing casualties that could survive a plane flight for evacuation to Japan via air. The Navy Log encourages you to listen to Wolf’s interview, which will provide a different, and often overlooked, perspective of the battlefield through the eyes of a field doctor.

Part One Becoming a Naval Officer in the Medical Corps and Receiving Orders to Korea with the First Marine Division

Part Three Traveling to the Chosin Reservoir and Treating the Marine and Army Wounded

Part Five Treating the Wounded at the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir

Part Two Participating in the Inchon Landings, Wonsan Landings, and Battle of Sudong-ni

Part Four Receiving Wounds from Mortar Fire at the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir

Part Six Returning Home and Service in the Navy Reserves

The Coast Guard played several crucial roles in the Korean War, and it is important that the branch’s contributions to the war effort do not go overlooked. Just before the start of World War II, the Coast Guard cordoned certain zones of water into sections specified as ocean stations. Within each of these zones, Coast Guard vessels would patrol, able to provide weather operations, offer aid to navigation, and assist distressed vessels anywhere within this ocean station. This system continued to be implemented through the Korean War. The Coast Guard even established three additional ocean stations in the North Pacific specifically aimed at supporting the war effort through weather data, search and rescue coverage, and navigational support. Throughout the war, twenty-four cutters—swift, midsized vessels—served in ocean stations that supported action in the Korean War, each of which carried teams of meteorologists, navigators, medical personnel, and rescue crews to support whatever task was required of them. The Navy Log contains the stories of many Coast Guardsmen who worked onboard these vessels, including Melvin Souza, who served onboard a weather ship, and Edward Clancy, who served onboard several cutters throughout his wartime service as an engineer. Make sure to check out Souza and Clancy’s stories on their Navy Log pages.

Arguably one of the most critical roles the Coast Guard played in the war was its role in search and rescue at sea. Here the Coast Guard cutter Vance is pictured with a PBM-5G Mariner seaplane flying over its deck. Planes like these were critical response aircraft called to recover service members in distress, most frequently pilots who had to bail out or were shot down over the sea. Were it not for the heroic actions of these Coast Guard search and rescue crews, a lot more service members would have surely perished at sea.

Melvin Bell in uniform at his duty station